On 22 May 1680, the German Classicist Johann George Graevius wrote from Utrecht to the French historian and classicist Adrien de Valois about the latter's upcoming edition of Ammianus Marcellinus. I have transcribed and translated the letter at the Last Historians of Rome blog, here. (The blog has been updated and you can now leave comments).

Ausonius

Saturday, 13 December 2025

Monday, 1 September 2025

Translating Ammianus Marcellinus, Book 14

1. How to fight the Isaurians (14.2.7)

And at times, our infantrymen were compelled to climb up high cliffs in order to pursue them, and even if they reached the mountaintops, grasping at thickets or brambles when their feet slipped, still they could not, in the narrow and trackless places, extend a battle line or gain a firm footing despite all their powerful efforts, since the ubiquitous enemy rolled broken rocks on to them from above; they either made a perilous withdrawal downhill or else, battling bravely in their desperate necessity, were flattened by the vast weights crashing down.

Therefore extreme caution was shown after that and when the marauders began to make for the mountain heights, the soldiers yielded to the unfavourable position. When, however, the Isaurians could be found on level ground, as constantly happened, they were allowed neither to stretch out their right arms nor poise their weapons, of which each carried two or three, but they were slaughtered like defenceless sheep.

Quam ob rem circumspecta cautela obseruatum est deinceps,| et cum edita montium petere coeperint grassatores,| loci iniquitati milites cedunt;| ubi autem in planitie potuerint repperiri,| quod contingit assidue,| nec exertare lacertos| nec crispare permissi tela quae uehunt bina uel terna| pecudum ritu inertium trucidantur.|

Accordingly, it has been the practice since that time to show circumspection and care; whenever the raiders start making for the highest uplands, the soldiers give up in the face of the unequal terrain. But whenever the Isaurians happen to be caught on the plain – which constantly happens – they are given no chance to thrust out their strong arms or to hurl the two or three javelins each of them carries, and they are slaughtered like helpless cattle.

2. Warding off the Isaurians near Laranda

There they were refreshed with food and rest, and after their fear had left them, they attacked some rich villages; but since they were aided by some cohorts of cavalry, which chanced to come up, the enemy withdrew without attempting any resistance on the level plain; but as they retreated, they summoned all the flower of their youth that had been left at home.

Ibi uictu recreati et quiete,| postquam abierat timor,| uicos opulentos adorti| equestrium adiumento cohortium, | quae casu propinquabant, | nec resistere planitie porrecta conati| digressi sunt, | retroque cedentes| omne iuuentutis robur relictum in sedibus acciuereunt.|

There they recovered their strength with food and sleep, and once their fear had left them, they attacked some opulent villages, but were with difficulty driven off, with help from some cavalry cohorts who happened to be nearby. And they made no attempt to resist on the broad plains, but withdrew, and, as they retreated, they called up all the strong young men who had been left at home.

3. Senior

officers with mixed loyalties (14.10.7-8)

But lo and behold, there arrived all of a sudden an informant with expertise in these regions, and after taking a payment he showed them a shallow place by night where the river could be forded. And with the enemy’s focus elsewhere, the army would have been able to cross here, not expected by anybody, and to create devastation everywhere, were it not that a few individuals from that nation, quibus erat honoratioris militis cura commissa, informed their countrymen of this attack through secret messengers – or so some thought. 8. At any rate, this suspicion blotted the reputation of Latinus the Count of the Domestici, Agilo the Tribune of the Stables, and Scudilo the commander of the Scutarii, who were respected at that time as if they carried the Republic in their own hands.

Friday, 12 May 2023

A detail in the manuscript transmission of Sidonius

I still haven’t made up my mind about Twitter (where I may be found as @GavinKellyLatin). On the one hand, there is all sorts of useful information and one discovers that all sorts of people one doesn’t know well or at all are humane, knowledgeable, and fascinating; on the other hand it reveals and encourages the posturing, sanctimony, and silliness of many others, and sometimes things darker than that. The following blogpost is the result of the positive side.

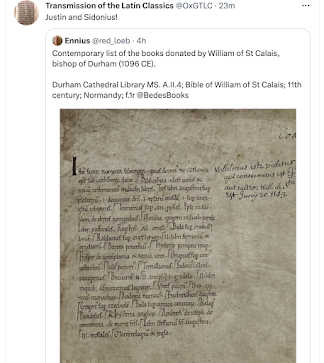

On 5 February ‘Ennius’ (@Red_Loeb) shared an image from a Durham manuscript, Cathedral Library A.II.4, the bible of William of St Calais, bishop of Durham, from AD 1096. This bible is said to originate in Normandy, like its owner. On f. 1v there is a list of the books that the bishop gifted to the library. In a retweet, my friend and colleague Justin Stover (‘Transmission of the Latin Classics’ = @OxGTLC), pointed out that it contained references to the works of Justin and Sidonius. Sure enough, two thirds of the way down you can see a paragraphus sign (¶) followed by Sidonius Sollius Panigericus. I forwarded it to Joop van Waarden who reproduced it on the sidonapol.org website.

There is a

potential significance to this observation. As Franz Dolveck has shown in his

chapter in the Edinburgh Companion to Sidonius Apollinaris (2020), Sidonius’

works were originally transmitted with the letters first and then the poems

(first panegyrics and then the shorter poems). Most extant manuscripts of

Sidonius begin with the letters and it would be their title that one would

expect to see. Indeed, Dolveck observes that ‘the manuscripts ‘containing only

the poems (which are very few in number) are late and all derive from more

complete manuscripts – in other words, they are the result of an editorial

choice to omit the letters’ (483). So much for the surviving manuscripts, but

Dolveck also shows that at one other point in the transmission a manuscript family

was formed from different sources for letters and poems. This is what he calls

the English family, consisting of six manuscripts from the late eleventh to

early thirteenth centuries: these are Dolveck’s numbers 19, 23, 35, 36, 38, 49:

-Hereford, Cathedral Library, O. II. 6 (Gloucester, s. XII2, letters only)

-London, British Library, Royal 4 B. IV (B) (Worcester, s. XII1, complete)

-Oxford, Bodleian Library, Auct. F. 5. 25 (‘maybe England’ (Dolveck), ‘French hand’ (Chronopoulos), s. XI2, less likely s. XII1, letters 1-5.3 with lacunae)

-Oxford, Bodleian Library, Digby 61 (olim B.N. 6) (s. XIIex, letters 3.12 to end and Carm. 1-2)

-Oxford, Bodleian Library, Rawl. G. 45 (England, s. XII, letters and poems with lacunae)

-Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, lat. 9551 (F) (England, s. XIII1/4, letters and poems)

In this family, the texts of the letters and of the poems come from separate sources. That of the letters lies fairly low in the stemma (a few steps below ζ in the stemma below), but that of the poems is close to the top (γ). Indeed, as I have suggested in a recent article on the paratexts of Sidonius’ poems (Kelly 2022, n. 8) the unity of γ and δ for the carmina is not wholly certain and there is a possibility that γ could be seen as a separate family.

The list from the Durham bible, it may be plausibly conjectured, fills in part of the story of this family. There was an authoritative text of Sidonius that omitted the letters and thus began with the Panegyrics. At some point it was combined with a text of the letters from a less excellent source and the oeuvre thus restored to its full length. Of course it is possible that the oldest of Dolveck’s English family, Oxford Auct. F. 5. 25, may not have contained the poems even before it was reduced to its current state, nor does Hereford O II. 6 contain them (Dolveck does not think any of the rest of the family are descended from these). William of St Calais’ manuscript, perhaps brought over with the Conqueror, could be either the source of the poems in this family, or perhaps a descendant or sibling of that source. At any rate, my main point is that England just after 1066 is exactly where you would expect to find evidence of a manuscript of Sidonius poems without the letters; it fits very nicely with Dolveck’s reconstruction.

Two further notes. First, the name Sidonius Sollius reverses the order of the two names Sidonius was most often known by. The manuscripts of the poems waver between giving the full glory of Sidonius’ nomenclature (Gaius Sollius Modestus Apollinaris Sidonius) and abbreviating in various ways: Modestus appears only very occasionally, though across the whole tradition, while some manuscripts shorten to GSAS or GSMAS. In the English family, the first panegyric is introduced thus: Gaii Sollii A. Sidonii panigerici dicti Anthemio augusto bis consuli praefatio incipit. The spelling panigericus, found in the Durham Bible, is absolutely consistent across the manuscripts of Sidonius.

Secondly, there are other fragmentary or partial manuscripts of Sidonius written in post-conquest England other those listed above (see Dolveck’s catalogue), and much other interesting material, including a life of Sidonius by none other than William of Malmesbury, and many glosses on manuscripts of the letters: Tina Chronopoulos has very well on written on both topics.

Works

cited

T.

Chronopoulos, ‘Brief lives of Sidonius,

Symmachus, and Fulgentius written in 12th-cent. England?’ Journal of Medieval Latin 20 (2010),

232–291.

T.

Chronopoulos, ‘Glossing Sidonius in the Middle Ages’, in G. Kelly and J. van

Waarden (eds), The Edinburgh Companion to Sidonius Apollinaris (Edinburgh,

2020), 643–664.

F. Dolveck,

‘The Manuscript Tradition of Sidonius’, in G. Kelly and J. van Waarden (eds), The

Edinburgh Companion to Sidonius Apollinaris (Edinburgh, 2020), 479–542. [The

first part of this chapter has been made freely available by the publisher

here]

G. Kelly,

‘Titles and Paratexts in the Collection of Sidonius’ Poems’, in A. Bruzzone, A.

Fo, and L. Piacente (eds), Metamorfosi del classico nell’età romanobarbarica

(SISMEL – Edizioni del Galluzzo: Florence, 2021 [2022]), 77–97. [I am not

allowed to post this on my website till five years after publication, but I

will happily send a copy to anybody who e-mails me; my text of the paratexts

can be found on the sidonapol.org website here].

Wednesday, 2 November 2022

Manuscripts and Early Editions of Ammianus Marcellinus, and How to Find Them

The digitisation of a high proportion of the surviving manuscripts of the Classics is one of the most transformative scholarly developments of the last decades, yet somewhat unsung. I thought it would be useful and interesting to list the manuscripts of Ammianus Marcellinus’ history. Unsurprisingly, the two crucial manuscripts from the Carolingian age, the Fuldensis and the fragmentary Hersfeldensis, are digitised – but so are 12 out of the other 16: it is a pity in particular that the Florence manuscript of Niccolò Niccoli, the first Italian copy and source of many of the rest, is not among them, and the same for the Venice manuscript that once belonged to Cardinal Bessarion and before that was filled with the annotations and corrections of Biondo Flavio. After that, I list and give links to the first 20 editions, a round number which takes us down to the immensely useful Variorum edition of Gronovius in 1693.

Manuscripts are assumed to be on vellum/ parchment unless otherwise indicated. To the bibliography on the liked websites you should add, for the Carolingian manuscripts, G.A.J. Kelly and J.A. Stover, ‘The Hersfeldensis and the Fuldensis of Ammianus Marcellinus: A Reconsideration’, Cambridge Classical Journal (2016), 62, 108-129 (available here or here). Although the Renaissance manuscripts, all of them Italian, are all derived from one of the two Carolingian ones, their study is of legitimate interest in itself. In the steps of Charles Upson Clark’s 1904 doctoral thesis and the many contributions of Rita Cappelletto in the 1970s and 1980s, I should signal the splendid doctoral thesis of Agnese Bargagna (‘Ammiano Marcellino e l’Umanesimo: tradizione e ricezione delle Res gestae a partire dai testimoni del xv sec. fino alle prime edizioni a stampa’, University of Macerata and Sorbonne University, 2020), downloadable here. Although I have seen many of the manuscripts in person as part of my preparations for my planned Oxford Classical Text, I should acknowledge having consulted Bargagna's work for many statements about these manuscripts below; moreover, what I say about them has no pretension to be comprehensive (for example, I have named only a selection of the known annotators).

For the editions, I have used above all the immensely useful work of Fred W. Jenkins, Ammianus Marcellinus: An Annotated Bibliography, 1474 to the Present (Leiden, 2017), whose recording of the precise titles I follow; see my review here and my supplements here.

And before beginning, I should add a stemma to indicate the manuscript relationships – it differs only very little from that of Charles Upson Clark from over 100 years ago.

A. Carolingian manuscripts

1. V: Fulda s. IX1/3 (the Fuldensis/ the Vaticanus). Vatican City, Vaticanus Latinus 1873: Contains books 14-31 (bifolium between 31.8.5 and 31.10.18 lost in the Renaissance); contains many annotations including contemporary correctors against the model (V2) and from the Renaissance (V3), including: Poggio Bracciolini (its rediscoverer), Niccolò Niccoli, Biondo Flavio, Pomponio Leto, Mariangelo Accursio. Digitisation.

Highlights: too many to mention, but observe the gap where the Greek of 17.4.17-23 was left out on ff. 41v-42f. Look for the difference a change of scribe can make on f. 58v, between lines 13 and 14. Scroll through and look at the omitted lines written in the margin. And look at the effects of a damaged exemplar in the lacunae of ff. 170v-172v in book 29.

f. 41v, where the scribe started recording a long passage of Greek, before deciding to leave it to a specialist who never appeared. See also the first half of an ownership mark in the top margin (it reads 'monasterii'; the word 'Fuldensis' is at the top of the next page. Two Renaissance scholars have left comments in the left-hand margin.

2. M: ?Fulda s. IX1/2 (the Hersfeldensis/ Marburgensis). Contains contemporary corrections and early modern ones probably in the hand of Sikmund Hruby z Jelení (Gelenius): Kassel, Landesbibliothek 4o Ms. chem. 31 (= 18.5.1 (1r) and 3 (1v), 18.6.12-15 (2r), and 16-17 (2v); both folia highly fragmentary). Digitisation + 2o Ms. philol. 27 (formerly in Marburg) (3r (formerly I) = 23.6.37-41, 3v (II) = 23.6.41-45; 4r (III) = 28.4.21-25, 4v (IV) = 28.4.25-29; 5r (V) 28.4.30-33, 5v (VI) = 28.4.34-5.2 (the first seven lines on each side have been cut from this folium); 6r (VII) = 28.5.11-6.1), 6v (VIII) = 28.6.1-5; 7r (IX) = 30.2.5-10, 7v (X) = 30.2.10-3.2 (this folium, which with f. 8 formed the central bifolium of a gathering, has been cut vertically so that about a third of the text is lost, at the start of the line recto and at the end of the line verso); 8r (XI) = 30.3.2-5, 8v (XII) = 30.3.5- 4.2). Digitisation.

Highlights: The beauty of the hand, which surpasses the scribes of the Fuldensis. You can see what are almost certainly Gelenius’ corrections on p. iv of the second set of fragments (4v), lines 13-14.

A. Renaissance manuscripts: copies of V

1. F: Florence, 1423 (copied by Niccolò Niccoli, on paper). Florence, San Marco J V 43.

Highlights: no digitisation, alas, but Niccoli had a very beautiful hand.

2. E: Rome, 1445 (circle of Poggio Bracciolini, on paper; contains annotations by various scholars including Poggio). Vatican City, Vaticanus Latinus 2969. Digitisation.

Highlights: the marginal and in-text corrections throughout as an intelligent humanist emends the text of V as he copies. There are also annotations by others, notably Poggio and an intelligent early sixteenth-century scholar.

3. N: Rome, 1455/1464 (Francesco Griffolini, Valesius’ ‘Codex Regius’, on paper, later emended against W after Biondo’s interventions (W2)). Paris, BNF, Parisinus Latinus 6120. Digitisation.

4. D: Rome, 1445/1457 (Pietro del Monte; on paper; stops at 25.3.13). Vatican City, Vaticanus Latinus 1874. Digitisation.

B. Renaissance manuscripts: copies of F

5. W: ?Florence, before 1455 (belonged to Biondo Flavio, who annotated it and collated against V (W2, 1455/1462), and Cardinal Bessarion; on paper). Venice, Marciana Z. 388.

Highlights: the acute emendations of Biondo, and his claim to remember a lost passage in book 16 from another manuscript. See R. Cappelletto, Ricuperi ammianei da Biondo Flavio (Rome, 1983).

6. K: Florence/ Cesena (copied by Iohannes Moguntinus, 1441/1460, for Malatesta Novello). Cesena, Malatestianus, S.XIV.4. Digitisation and Catalogue.

Highlight: a fine illuminated capital in this luxury manuscript.

7. Y (also Z): copied at Florence, contains annotations by Antonio Beccadelli (Panormita, d. 1471). Vatican City, Vaticanus Latinus 3341. Digitisation.

8. U: copied at Florence for Federico da Montefeltro (d. 1482) by Nicolaus Antonii de Ricciis, working closely with Vespasiano da Bisticci. Vatican City, Urbinas Latinus 416. Digitisation.

Highlights: sheer beauty (pity about the slip in the author's name!)

9. Q: copied at Florence, 1488 (Alessandro da Varrazzano). Modena, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Estense, Lat. 425 = alfa.Q.4.7. Catalogue.

10. C: Italy, s. XVex (Codex Colbertinus, on paper); Paris, BNF, Parisinus Latinus 5821 (runs from 15.1.3 to 31.15.9, thereafter fragmentary until 31.16.2). Digitisation.

C. Renaissance manuscripts: copies of W

11. H: 1462 (copied by Petrus Honestus for Gregorio Loli Piccolomini, cousin and secretary of Pius II, from W after the interventions of Biondo (W2)). Paris, BNF, Parisinus Latinus 5819. Digitisation.

12. T: c. 1467 (Tolosanus; copied for Giovanni Stefano Bottigella, bishop of Cremona 1467-1476; from W): Paris, BNF, Parisinus Latinus 5820. Digitisation.

D. Renaissance manuscripts: copies of o (a lost copy of F).

13. P: probably before 1434 (Petrinus; for the Orsini family, probably Cardinal Giordano Orsini, d. 1434) Vatican City, Archivio Capitolare di San Pietro E. 27 (books 14 to 26). Digitisation.

Highlight: an illuminated first capital. 19th-century scholars thought that P was a witness to a different pre-Poggio tradition. Not so, but it is very attractive:

14. R: between 1423 and 1474, probably later in the period (source of Sabinus’ editio princeps, 1474) Vatican City, Reginensis Latinus 1994 (books 14 to 26 only). Digitisation.

E. Renaissance florilegia

15. Excerpta, especially on geography, 1455/1465 (Pomponio Leto, from N). Vatican City, Vaticanus Latinus 7190, 104r-123v. Digitisation. For the identification of the copyist, see A. Bargagna, ‘Gli excerpta ammianei del Vat. Lat. 7190 e uno sguardo sullo studio pomponiano delle Res Gestae’, Sileno 47 (2021), 9-47.

16. Excerpta with ‘Summa rerum sex Caesarum ex Ammiano Marcellino, s. XV, Padua (Marco Lucio Fazini, Padua), Biblioteca del Seminario Vescovile MS. 288, 112r-135r.

Editions of Ammianus Marcellinus

1. S = Sabinus, Rome, 1474. Sabinus, Angelus, Ammiani Marcellini rerum gestarum liber quartusdecimus. Rome: Georgius Sachsel and Bartholomaeus Golsch, June 7, 1474. Books 14-26 only. Digitisation.

Highlight: quite how bad the text is.

2. B = Castellus, Bologna, 1517. Ammiani Marcellini opus castigatissimu(m) nuper a Petro Castello instauratum omni cura ac diligentia, ab infinitimis errorum monstris enixissimo labore vindicatum et multa quae hactenus desiderabantur ad professorum utilitaem sunt addita. Bononiae: Ammianum Marcellinum historicum typis excussoribus impressit Hieronymus de Benedictis Bononiensis …, 1517. Books 14-26 only. Digitisation.

Highlight: the recherché hendecasyllabic poem written for the frontispiece by Giovanni Battista Pio. Pio's involvement and the choice of marginal keywords make it clear that Ammianus was of interest for his exotic vocabulary.

3. b1 = ‘Erasmus’, Basel, 1518 (in fact the responsibility of Beatus Rhenanus). Ex recognitione Des. Erasmi Roterodami C. Suetonius Tranquillus. Dion Cassius Nicaeus. Aelius Spartianus. Iulius Capitolinus. Aelius Lampridius Vulcatius Gallicanus V.C. Trebellius Pollio. Flavius Vopiscus Syracusius. Quibus adiuncti sunt Sex. Aurelius Victor. Eutropius. Paulus Diaconus. Ammianus Marcellinus. Pomponius Laetius Ro. Io. Bap. Egnatius Venetus. Basileae: Apud Iohannem Frobenium, 1518. pp. 564-768: books 14-26 only; reprints B with few changes. The copy linked to here was given by Froben to the Augsburg humanist Konrad Peutinger. Digitisation.

4. b2 = Reprint of ‘Erasmus’ edition, Cologne, 1527. Ex recognitione Des. Erasmi Roterodami, C. SuetoniusTranquillus. Dion Cassius Nicaeus. Aelius Spartianus. Iulius Capitolinus. Aelius Lampridius Vulcatius Gallicanus V.C. Trebellius Pollio. Flavius Vopiscus Syracusius. Quibus adiuncti sunt Sex. Aurelius Victor. Eutropius. Paulus Diaconus. Ammianus Marcellinus. Pomponius Laetius Ro. Io. Bap. Egnatius Venetus. Coloniae: In aedibus Eucharij Cervicorni, 1527. pp. 429-584: books 14–26 only. Digitisation.

5. A = Accursius (Augsburg, 1 April 1533): Accursius, Mariangelus, Ammianus Marcellinus a Mariangelo Accursio mendis quinque millibus purgatus, & libris quinque auctus ultimis, nunc primum ab eodem inventis. Augustae Vindelicorum: In Aedibus Silvani Otmar, 1533. Books 14-31. Digitisation.

Highlights: The editio princeps of books 27-31! Accursius' claim to have corrected 5000 errors from Castellus' edition (which may not be far off); the copyright in the name of the Pope, the Emperor, and the Republic of Venice.

6. G = Sigismundus Gelenius (Basel, 1533): Ammiani Marcellini Rerum Gestarum Libri XVII Quorum Postremi IIII. Nunc Primum Excusi, in Omnia quam antehac emendatiora. Annotationes Des. Erasmi & Egnatii cognitu dignae. C. Suetonius Tranquillus. Dion Cassius. Aelius Spartianus. Iulius Capitolinus. Aelius Lampridius. Vulcatius Gallicanus. Trebellius Pollio. Flavius Vopiscus. Herodianus Politiano interp. Sex. Aurelius Victor. Pomponius Laetus. Io. Baptista Egnatius. Ammianus Marcellinus quatuor libris auctus. Cum indicibus copiosis. Basileae: In Officina Frobeniana, 1533. Books 14–30.9.6 of Ammianus are found on pp. 545–786. Digitisation.

Highlights: Gelenius' textual acuity; Froben's preface on p. 546, explaining how they borrowed the Hersfeld manuscript (M) from the Abbot and used to it to restore numerous passages; the long passage of Greek missing from V and all surviving manuscripts - the largest of the many additions introduced from the now lost parts of M - on p. 598.

7. Robertus Stephanus (Robert Estienne) (Paris, 1544) Ammiani Marcellini Rerum gestarum libri XVIII à decimoquarto ad trigesimum primum. nam XIII priores desiderantur. Quanto vero castigatior hic scriptor nunc prodeat, ex Hieronymi Frobenii epistola, quam hac de causa addimus, cognosces. Librum trigesimum primum qui in exemplari Frobeniano non habetur, adiecimus ex codice Mariangeli Accursii. Parisiis: Ex officina Rob. Stephani typographi Regij, 1544. A reprint of Gelenius, with book 31 added from Accursius (chapter 30.10 was left out). Digitisation.

8. G2 = Gelenius’ second edition, Basel 1546. Vitae Caesarum quarum scriptores hi C. Suetonius Tranquillus, Dion Cassius, Aelius Spartianus, Iulius Capitolinus, Aelius Lampridius, Vulcatius Gallicanus, Trebellius Pollio, Flavius Vopiscus, Herodianus, Sex. Aurelius Victor, Pomponius Laetus, Io. Baptista Egnatius, Eutropius libri X integritati pristinae redditi, Ammianus Marcellinus longe alius quam antehac unquam. Annotationes D. Erasmi Rot. & Baptistae Egnatij in vitas Caess. Accesserunt in hac editione Velleii Paterculi libri II ab innumeris denuo vendicati erroribus, addito Indice copiosissimo. Basileae: Froben, 1546. This, like subsequent editions mentioned, contains all 18 books: from pp. 473-681. Digitisation.

9. Gryphius, Lyon 1552. Ammiani Marcellini rerum gestarum libri decem et octo. Lugd.: Apud Seb. Gryphium, 1552. Digitisation.

10. Henricus Stephanus, Geneva, 1568. Varii historiae romanae scriptores, partim Graeci, partim Latini, in unum velut corpus redacti, De rebus gestis ab Urbe condita usque ad imperii Constantinopolin translati tempora. 4 vols. Excudebat Henricus Stephanus, 1568. Digitisation.

11. Syllberg, Frankfurt, 1588. Sylburg, Friedrich. Historiae Augustae scriptores latini minores; qui Augustorum, necnon et Caesarum tyrannorumque in Romano imperio vitas ad posteritatem litterarum monumentis propagarunt: Suetonius Tranquillus: Aelius Spartianus: Iulius Capitolinus:Vocatius Gallicanus: Aelius Lampridius: Trebellius Pollio: Flavius Vopiscus: Ammianus Marcellinus. Adiecti sunt et recentiores historiae continuatores; Pomponius Laetus, Ioan. Baptista Egnatius. Item Ausonii Burdeg. epigrammata in Caesares romanos: Imperatorum catologus: Romanae urbis descriptio. Additae in eosdem adnotationes Ioannis Baptistae Egnatii, et Erasmi Roterodami; cum Henrici Glareani et Theodori Pulmani adnotationibus in Suetonium. Ad haec graecorum allegantur, interpretatio nova: et rerum verborum notatu digniorum Index amplissimus: opera Friderici Sylburgii. Tomus alter. Francofurdi: Apud Andreae Wecheli heredes, Claudium Marnium and Ioan. Aubrium, 1588. Ammianus is on pp. 2.304-518. Digitisation.

12. Le Preux, Lyon, 1591. Ammiani Marcellini Rerum sub Impp. Constantio, Iuliano, Ioviano, Valentiniano et Valente, per xxvj annos gestarum historia, libris XVIII comprehensa, qui e xxxj hodie supersunt. Cui nunc primum accesserunt breviaria singulis libris praefixa. Perpetuae ad marginem Notae morales ac politicae. Chronologia Marcelliniana, seu Temporum supputatio, ab Imperio Nervae usque ad Valentis obitum. instar brevis alicuius Supplementi xiiij priorum librorum, qui temporis iniuria perierunt. Gnomonologia Marcelliniana. Orationum et Rerum insignium Index. Lugduni: Apud Franciscum Le Preux, 1591. Digitisation.

13. Le Preux, Lyon, 1600. Ammiani Marcellini Rerum sub Impp. Constantio, Iuliano, Ioviano, Valentiniano et Valente, per xxvj annos gestarum historia, libris XVIII comprehensa, qui e xxxj hodie supersunt. Cui nunc primum accesserunt breviaria singulis libris praefixa. Perpetuae ad marginem Notae morales ac politicae. Chronologia Marcelliniana, seu Temporum supputatio, ab imperio Nervae usque ad Valentis obitum. instar brevis alicuius Supplementi xiiij priorum librorum, qui temporis iniuria perierunt. Gnomonologia Marcelliniana. Orationum et Rerum insignium Index. Lugduni: Apud Franciscum Le Preux, 1600. A reprint of the 1591 edition. Digitisation.

14. The Geneva Corpus, 1609. Historiae Romanae Scriptores Latini Veteres, Qui Extant Omnes, Qui Regum, Consulum, Caesarum Res gestas ab urbe condita continentes: nunc primum in unum redacti corpus, duobus Tomis distinctum copiosissimóque non vero modò, sed etiam verborum & phraseωn notatu digniorum indice, locupletatum: in quo non historici solum, verùm etiam Iurisconsulti, Politici, Medici, Mathematici, Rhetores, Grammatici, quin et theologi atque adeo pene omnium disciplinarum Professores, quod usibus ipsorum inservire queat, invenient. 2 vols. Aureliae Allobrogum: Petrus de la Roviere, 1609. For Ammianus see volume 2, pp. 411-556. Digitisation.

15. Friedrich Lindenbrog, Hamburg, 1609. Ammiani Marcellini Rerum Gestarum Qui De XXXI. Supersunt Libri XVIII. Ad fidem MS. & veterum Codd. recensiti, et Observationibus illustrati ex bibliotheca Fr. Lindenbrogi. Hamburgi: Ex Bibliopolio Frobeniano, 1609. Digitisation.

Highlight: the first really detailed and scholarly annotations

16. Janus Gruterus, Hannover, 1611. Historiae Augustae Scriptores Latini minores, A Iulio fere Caesare ad Carolum Magnum: L. Annaeus Florus. Velleius Paterculus. C. Suetonius Tranquillus. Aelius Spartianus. Iulius Capitolinus. Vulcatius Gallianus. Aelius Lampridius. Trebellius Pollio. Flavius Vopiscus. Ammianus Marcellinus. Aurelius Victor. Paulus Diaconus. Landulphus Sagax. Iornandes, &c. Priores quidem, ex optimâ cuiusque Editione, Comparati Confirmatique ad codices MSS. Bibliothecae Palatinae: Posteriores verò Mille Locis Emendati Suppleti operâ Jani Gruteri Cuius etiam additae Notae. Hanoviae: Impensis Claudii Marnii heredum …, 1611. Ammianus on pp. 453-691. Digitisation and Notes (starts with new pagination after p. 127):

17. Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn, Leiden, 1632. Ammiani Marcellini Rerum Gestarum Quae extant. M. Boxhorn Zuerius Recensuit et Animadversionibus illustravit. Historiae augustae scriptorum minorum latinorum, 4. Lugduni Batavorum: Ex officinâ Joannis Maire, 1632. Digitisation.

18. Henricus Valesius (Henri de Valois), Paris, 1636. Ammiani Marcellini Rerum Gestarum Qui De XXXI. Supersunt Libri XVIII. Ex MS. Codicibus emendati ab Henrico Valesio & Annotationibus illustrati. Adjecta sunt Excerpta de gestis Constantini nondum edita. Parisiis: Apud Joannem Camusat …, 1636. Digitisation.

19. Hadrianus Valesius (Adrien de Valois), Paris, 1681. Ammiani Marcellini Rerum Gestarum Qui de XXXI. Supersunt, Libri XVIII. ope MSS. codicum emendati a Henrico Valesio, et auctioribus Adnotationibus illustrati. Necnon Excerpta vetera de Gestis Constantini et Regum Italiae. Editio Posterior, Cui HadrianusValesius, Historiographus Regius, Fr. Lindenbrogii JC in eumdem Historicum ampliores Observationes, et Collectanea Variarum Lectionum adjecit; et beneficio codicis Colbertini Ammianum multis in locis emendavit, Notisque explicuit: Disceptationem suam de Hebdomo, ac Indicem rerum memorabilium subjunxit. Praefixit et Praefationem suam, ac Vitam Ammiani à Claudio Chiffletio JC compositum. Parisiis: Ex Officina Antonii Dezallier …, 1681. Digitisation.

20. Jacobus Gronovius, Leiden, 1693. Ammiani Marcellini Rerum Gestarum, Qui de XXXI Supersunt, Libri XVIII. Ope MSS. codicum emendati ab Frederico Lindenbrogio & Henrico Hadrianoque Valesiis cum eorundem integris Observationibus & Annotationibus, Item Excerpta vetera de Gestis Constantini et Regum Italiae. Lugduni Batavorum: Apud Petrum van der Aa, 1693. Digitisation.

Highlights: The notes of his predecessors and himself are conveniently laid out at the bottom of the page. There are splendid illustrations of the battle of Strasbourg and the siege of Amida (below).